Tobias Siegenthaler – Reading the Bible as Narrative

Includes BONUS Blog Post (scroll down to read)

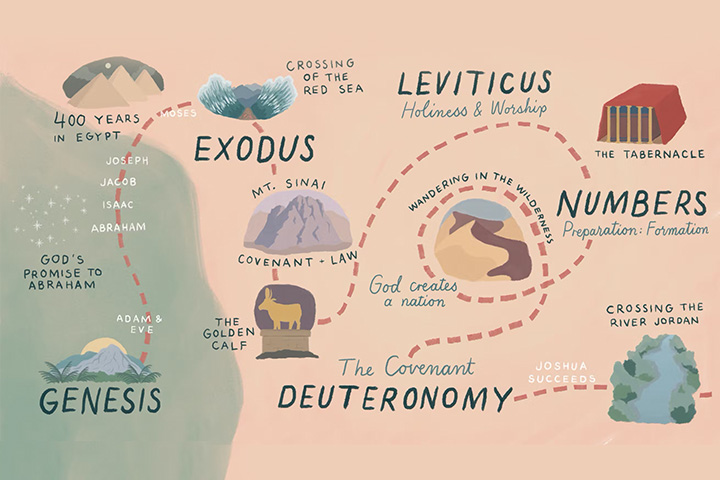

In this conversation, we look at how developing awareness of the interplay in the Bible between New Testament and Hebrew scriptures with regards to literary and narrative links and how reading with this in mind can open our eyes to fresh ways of understanding the text for our world. We do hope you enjoy listening to our fourth episode of the TheoDisc Podcast!

In this conversation, we look at how developing awareness of the interplay in the Bible between New Testament and Hebrew scriptures with regards to literary and narrative links and how reading with this in mind can open our eyes to fresh ways of understanding the text for our world. We do hope you enjoy listening to our fourth episode of the TheoDisc Podcast!

Tobias Siegenthaler grew up in Switzerland surrounded by mountains and nature. After completing school his interest for theology was awakened by reading Bonhoeffer’s letters from prison. In the following years he studied theology and completed an apprenticeship as a metal-worker. For some time he worked in construction and later, for several years, caring for migrants from different backgrounds. Next to that he was employed by different churches, which formed his understanding of ministry. He is currently working on his PhD thesis, which focuses on how the gospel of Luke picks up patterns from the Joseph-narratives in Genesis to tell the story about Jesus. In his leisure time he still enjoys nature and sports.

Episode 4 Outline:

- Start-01:20 – Introduction

- 01:24-06:30 – Welcome to Tobias and 3 questions.

- 06:38-11:51 – What does a narrative approach to the Bible look like and how does this compare and contrast to other views, like the historical approach?

- 12:00-15:42 – Looking at the biblical writers as literary authors in their own right, and not only writers of historical fact, with various examples.

- 15:50-23:17 – How do we read the Gospels narratively? Reference is made to specific stories in the Old Testament through two examples.

- 23:26-26:57 – How do we deal with this idea of the unity of Scripture? In what ways can we make the narrative approach to the Bible more accessible?

- 27:05-32:33 – Thinking of how the idea of ‘one meaning’ to a biblical passage is often proclaimed, how can we, through a narrative approach to Scripture, find our stories within the overall Story of the Gospel itself?

- 32:33-End – Closing information

NEXT EPISODE – Bob Ekblad on ‘Christian Nationalism’

Find us wherever you find good podcasts!

BONUS BLOG POST

Reading Patterns in the Biblical Narrative – Joseph

A good book invites the reader into its world. It lets us anticipate the development of the story while also surprising us with unexpected twists and turns. When 007 is trapped in a room with the villain, we are not surprised when he pulls out special gadget to defeat his opponent. We have learnt that M is in charge of developing and supplying special equipment for the secret agent. In the Bible, the narrative works in similar ways.

Let me give you an example: Joseph, the main character and saviour figure of the last section of the book of Genesis – the Biblical 007 if you want – is imprisoned in Egypt. He’s at the very bottom, in the “pit” (Gen 40:15), a place where only the criminals or the already half-dead are residing. How does he get out of there? Well, Pharaoh has a couple of bad dreams that stir him up. None of his wise men can explain his dreams, which really messes up his day. In that moment, one of his chief-officials – let’s call him the wine-man – remembers Joseph whom he had met a couple of years earlier when Pharaoh suspected him of some shady business. When wine-man tells Pharaoh about Joseph and his special dream-interpretation gift, Joseph is brought out of his hole, given a nice shave and presented to Pharaoh. He interprets Pharaoh’s dream, who is so impressed that he makes Joseph prime-minister of his kingdom, imparting his royal authority on him by giving him his signet-ring and dressing him up.

Let me give you an example: Joseph, the main character and saviour figure of the last section of the book of Genesis – the Biblical 007 if you want – is imprisoned in Egypt. He’s at the very bottom, in the “pit” (Gen 40:15), a place where only the criminals or the already half-dead are residing. How does he get out of there? Well, Pharaoh has a couple of bad dreams that stir him up. None of his wise men can explain his dreams, which really messes up his day. In that moment, one of his chief-officials – let’s call him the wine-man – remembers Joseph whom he had met a couple of years earlier when Pharaoh suspected him of some shady business. When wine-man tells Pharaoh about Joseph and his special dream-interpretation gift, Joseph is brought out of his hole, given a nice shave and presented to Pharaoh. He interprets Pharaoh’s dream, who is so impressed that he makes Joseph prime-minister of his kingdom, imparting his royal authority on him by giving him his signet-ring and dressing him up.

When we later read the Bible books of Esther and Daniel, we can see the authors playing with this narrative pattern. Esther and Mordechai, the two heroes of the little scroll, are not cast into a pit. However, their people, the Judeans, have been condemned to death by a royal edict. Sitting on “death-row” Mordechai hatches a plan to turn things around. He asks Esther, his niece and newly made queen, to go to the king and stop this madness. She follows Mordecai’s instructions but does not tell the king right away about the plight of her people, simply inviting him and Haman, the bad guy, to a cocktail-party. She knows she has to get the king in the right mood to be able to turn things around. At the first party, she simply asks her two guests to come to her once again the following day. The night in between the king cannot sleep. In his insomnia he reads his royal memoirs and is reminded of how Mordechai had formerly saved his life. Subsequently, he fetches Mordechai and honours him much in the way Joseph was honoured: He is dressed in the king’s robes and ridden on his horse. However, he does not give him the royal signet-ring. That one is still in the hand of Mordechai’s opponent and henchman, Haman. At Esther’s second drinking party, the tides turn on Haman: Haman impaled on the gallows that he had set up for Mordechai and the king’s signet-ring is given to Mordechai. There are more parallels between these two stories, but you get the idea.

When we later read the Bible books of Esther and Daniel, we can see the authors playing with this narrative pattern. Esther and Mordechai, the two heroes of the little scroll, are not cast into a pit. However, their people, the Judeans, have been condemned to death by a royal edict. Sitting on “death-row” Mordechai hatches a plan to turn things around. He asks Esther, his niece and newly made queen, to go to the king and stop this madness. She follows Mordecai’s instructions but does not tell the king right away about the plight of her people, simply inviting him and Haman, the bad guy, to a cocktail-party. She knows she has to get the king in the right mood to be able to turn things around. At the first party, she simply asks her two guests to come to her once again the following day. The night in between the king cannot sleep. In his insomnia he reads his royal memoirs and is reminded of how Mordechai had formerly saved his life. Subsequently, he fetches Mordechai and honours him much in the way Joseph was honoured: He is dressed in the king’s robes and ridden on his horse. However, he does not give him the royal signet-ring. That one is still in the hand of Mordechai’s opponent and henchman, Haman. At Esther’s second drinking party, the tides turn on Haman: Haman impaled on the gallows that he had set up for Mordechai and the king’s signet-ring is given to Mordechai. There are more parallels between these two stories, but you get the idea.

In Daniel, the king has a dream but his courtiers cannot interpret it, nor even tell the king what the content of his dream was. Knowledge of the Joseph narrative raises our expectations: Daniel is brought before the king and he tells him his dream and its interpretation. Daniel is super-Joseph – not only can he interpret the king’s dream, but he is even able to reveal the content of the nocturnal vision. The king is impressed, falls on his face before Daniel and acknowledges that Daniel’s God is above all the other gods. Daniel is made great in the kingdom and his friends are given high positions on the royal court. When his friends are later cast into a fiery furnace because they did not bow to the statue erected by the king, we should again remember Joseph. This is also true a few chapters onwards when Daniel himself is cast into a pit because he was praying to God against a royal edict made to entrap him. This pit, which has lions in it, is sealed with the royal signet-ring and cannot be opened before the break of dawn. The king, who has now realised that the edict he validated was targeting his extraordinary courtier, cannot sleep. Subsequently, we are not surprised that it is the king himself who brings Daniel out of that fateful pit. Furthermore, he acknowledges Daniel’s God and Daniel, like Joseph, is described as successful in the royal court.

In Daniel, the king has a dream but his courtiers cannot interpret it, nor even tell the king what the content of his dream was. Knowledge of the Joseph narrative raises our expectations: Daniel is brought before the king and he tells him his dream and its interpretation. Daniel is super-Joseph – not only can he interpret the king’s dream, but he is even able to reveal the content of the nocturnal vision. The king is impressed, falls on his face before Daniel and acknowledges that Daniel’s God is above all the other gods. Daniel is made great in the kingdom and his friends are given high positions on the royal court. When his friends are later cast into a fiery furnace because they did not bow to the statue erected by the king, we should again remember Joseph. This is also true a few chapters onwards when Daniel himself is cast into a pit because he was praying to God against a royal edict made to entrap him. This pit, which has lions in it, is sealed with the royal signet-ring and cannot be opened before the break of dawn. The king, who has now realised that the edict he validated was targeting his extraordinary courtier, cannot sleep. Subsequently, we are not surprised that it is the king himself who brings Daniel out of that fateful pit. Furthermore, he acknowledges Daniel’s God and Daniel, like Joseph, is described as successful in the royal court.

By the time we come to the New Testament in the Bible the pattern is fairly established: nocturnal disturbances of the king’s sleep lead to the salvation and elevation of the main hero of the story. Thus, when Jesus stands before Pilate (the deputy of the Roman Caesar) and his wife recounts a dream she has had (Mt 27:19), we expect that Jesus will be finally delivered from his attackers and given royal status and power. However, in Jesus’ case this expectation is disappointed in a curious way. Though Jesus still receives all the royal insignia – they dress him in a purple robe, place a crown on his head and a sceptre in his hand, fall on their knees before him and hail him as king of the Jews (Mt 27:27-29) – these insignia are all given to mock him rather than to give him the position we had anticipated. Here, the established pattern is used to demonstrate in starkest contrast what is happening. The king of the Roman empire does not save Jesus from the ‘pit’. Rather Jesus is crucified by the Romans and buried in a tomb which belongs to a guy with the name of Joseph (Mt 27:57-60). The Roman soldiers make sure Joseph’s tomb is sealed of to make sure Jesus’ body is not stolen (Mt 27:66). The Roman emperor and king does not save Jesus from his pit. However, there is another King who raises him out of the pit. And though he is not given a royal signet-ring, he is placed on the throne of the heavenly kingdom and given authority over it – a kingdom which is beyond and above any empire, Roman or otherwise.

By the time we come to the New Testament in the Bible the pattern is fairly established: nocturnal disturbances of the king’s sleep lead to the salvation and elevation of the main hero of the story. Thus, when Jesus stands before Pilate (the deputy of the Roman Caesar) and his wife recounts a dream she has had (Mt 27:19), we expect that Jesus will be finally delivered from his attackers and given royal status and power. However, in Jesus’ case this expectation is disappointed in a curious way. Though Jesus still receives all the royal insignia – they dress him in a purple robe, place a crown on his head and a sceptre in his hand, fall on their knees before him and hail him as king of the Jews (Mt 27:27-29) – these insignia are all given to mock him rather than to give him the position we had anticipated. Here, the established pattern is used to demonstrate in starkest contrast what is happening. The king of the Roman empire does not save Jesus from the ‘pit’. Rather Jesus is crucified by the Romans and buried in a tomb which belongs to a guy with the name of Joseph (Mt 27:57-60). The Roman soldiers make sure Joseph’s tomb is sealed of to make sure Jesus’ body is not stolen (Mt 27:66). The Roman emperor and king does not save Jesus from his pit. However, there is another King who raises him out of the pit. And though he is not given a royal signet-ring, he is placed on the throne of the heavenly kingdom and given authority over it – a kingdom which is beyond and above any empire, Roman or otherwise.

Tracing such narrative patterns is what we do when we hear a song on the radio that picks up a theme from Beethoven’s Fifth, or when we watch a movie and the main character is riding on a horse through the wilderness. Our brains are wired to learn and figure out the patterns according to which the world runs. This ensures that our everyday life is not full of surprises. We know what to expect on a Monday morning on our commute to work. But with God, there are still enough surprises around the corner that transform the story. And maybe next time we are cast into a pit of winter-depression, we might be called out to interpret someone’s dream, so that they can find new meaning and purpose in life.

TheoDisc Podcast

TheoDisc is a podcast by WTC faculty and friends where we present theological ideas in an accessible way that will hopefully stimulate you to pursue your own theological learning and ultimately to deepen your faith. It is a place of discussion and debate, and a place to hear a variety of voices. We do hope you enjoy listening!

-

SLON Hub Closure

19 March 2024 -

Nick Crawley - Bible for Life

19 July 2023 -

Jack Johnson - Prayer

5 July 2023 -

Matthew Lynch - Flood and Fury

21 June 2023 -

Matthew Bates - Why the Gospel?

7 June 2023 -

Jason Myers - Paul, Politics, and Pragmatism

24 May 2023 -

Adesola Akala - Glory in the Gospel of John

10 May 2023 -

Ali Blacklee Whittall - Seeing the Women of the OT

26 April 2023 -

Ruth Perrin and Ed Earnshaw - Student Ministry

12 April 2023