Hungry Bellies

A few things have happened to me in the past few months that have made me want to write something on the fact that seemingly very few Christians are reading the Bible and engaging in theological reflection, why this might be the case, and what we’re doing about it.

In doing this, I’m assuming that studying the Scriptures and engaging in theological reflection is a good thing for Christians to do. I wrote a bit about that a while ago in relation to charismatics here.

One of the things that got me thinking is that this year I processed the bulk of our applications for the coming year. That job normally falls to Matt as the Academic Dean, but as he was on sabbatical, I got to do it. I loved it, actually—reading through the reasons that people want to put their time, money, and effort into studying theology—getting to read some of their stories and some of their hopes and fears—while all the time knowing what’s ahead of them when they arrive and knowing that they’re going to love it!

The two words that stood out more than any other in the applications were “hunger” and “depth.” People are hungry, and they want something of substance to be “eating”. I’m assuming that all the people starting at the other theological colleges this September have written similar things.

The second thing that happened was that I spoke at New Wine, giving the main Bible talks. I thought it was brave of Paul Harcourt and his team to ask me. I’m not well known and I’m mainly now an academic although I have been involved in church leadership for 30 years. I’ve heard hundreds of talks in my charismatic evangelical world and I know what people are accustomed to from that kind of mainstage presence. But as I was preparing for New Wine, I also knew that I wasn’t going to be able to follow any kind of ‘style’, and that I was just going to have to be myself.

What I did in the end was essentially to give six WTC-style lectures. Now I know for sure that I won’t have been everybody’s cup of tea, and I’ve learned over the years that most Christians in our circle here in the UK are too polite to say when they don’t like something. So most of us probably only get the positive feedback in the end. Nevertheless, I think that what I saw in the way that people fed back to me was that a lot of people had found doing Bible study and theology like that thought-provoking and rewarding. I have a joke with my friend, Lindsey Hall, about our lovely mutual friend Gavin D’Costa who turned to me once after an academic discussion and said, “Well that was thrilling!” So nerdy, but so true.

The third thing was that Tim Brearley from Bible Society asked me and my husband, Nick, if we would do a short video for them on why we thought people didn’t read the Bible and what we thought could be done about it. I think we must have talked with Tim for about three hours all in all for a 3-4 minute video! We were all fascinated by the topic and talked around loads of different themes. Tim asked us some great questions and got us thinking.

The fourth thing was Nick launching his Bible for Life website in a great new format – all based on eating a substantial multi-course meal of the Spirit! I realized how effective he is being in providing a resource that could enable this generation to engage with Scripture in ways that are fruitful, accessible, and interesting—at no cost apart from just putting the time in. His background as a good evangelical and a Navigator have been put to great use for something much more exciting than ticking off your quiet time every morning. After years of young men and women seeking him out to study the Bible with him, I’ve been encouraging him to write something on how to engage with Scripture. Look up Bible for Life and watch this space. https://bibleforlife.co.uk/

The last thing was something that has stayed with me since March. A great friend of mine, Tina Cooke, travelled to Winchester from London to hear my Lent Lectures, which meant a lot to me. I think the lectures were a bit too dense really and not as thrilling as they might have been. But Tina wrote me a beautiful email in response and included this. “I turned to my neighbour and said, ‘The thing is, you don’t realize how thirsty you are until someone puts a glass of water in front of you.’”

Hunger, thirst, depth. People are hungry – they want to be eating solid food. I know they are. And the Bible is a fascinating book. It is also food for the soul.

Food for the Soul

I don’t really know how this works, and I know that it is Jesus, the Word, who is the bread of life, but there is also something about the word of God in the Scriptures that feeds us. In Jeremiah we read, “When your words came, I ate them; they were my joy and my heart’s delight…” (Jer 15:16). Jesus declares that “human beings shall not live on bread alone, but on every word that comes from the mouth of God.” (Matt 4:4) The word of God is associated with food—it can fill our spiritual bellies if we are actually eating what is given us. It is nourishing, satisfying, nutritious, delicious.

So why are we not sitting down to eat?

The Bible is Unfamiliar

I think one of the reasons is that the Bible is unfamiliar and people don’t know where to start or how to make sense of a lot of what they read and so they give up. It’s a great legacy of the Reformation that we can have Bibles in our own language in our hands and on our phones, but I don’t think it helps us to think that the Bible is always just self-explanatory so we can all be left to it.[1] The Bible needs to be taught and it’s a much more fascinating book if it is. I love hearing great Bible teachers telling me something about the context and the language that I didn’t know that brings the text to life.

The Bible is unfamiliar because it’s not read at home or in schools in the way that it would have been in the past. Church is now the only place where most people will encounter the Bible, so preachers and teachers need to take that responsibility seriously. For some reason, however, Bible teaching has gone out of fashion in evangelical charismatic churches. I don’t really understand this, but just from conversations I think there are a few things going on.

The first is that I think leaders have made assumptions about people in the congregation just getting on with it when they’re not. The second thing is that I’m unsure about whether leaders are immersed in the Scriptures. Put it this way, if they are, it’s not filtering through. The third is that I think there is a fear that in-depth teaching will be perceived to be boring, put people off, and they won’t come back.

Teaching or Inspiration?

Consequently, a lot of what we hear is a few verses from the Bible used as a springboard for a talk that is largely made up of stories, life wisdom, and maybe a few jokes. I love hearing testimonies and stories of what God is doing around the world, and it can be hugely inspirational, but it’s not teaching. The same can be said for interviews. I like people and I like hearing about what has motivated them in their lives, but it doesn’t serve the same purpose as teaching. Much of what we get at festivals and also in our local churches falls in these categories, which would be fine if we were also receiving good teaching, but I think we all know that for the most part, it’s become the main event.

The one thing that I have heard particularly in charismatic circles is the skill or gift to take a story from the Bible, work through it, and apply it to our lives today. I’ve heard some people do that brilliantly and prophetically. It strikes me that this is teaching, and I think it is a good thing.

Even so, just taking stories or working through themes as a practice for the preaching series can mean that communities never really engage with the whole of the Bible. Communities of believers should work through books (or the lectionary), so as to ensure that we’re engaging with the Scriptures on its own terms and not just ours. Let the Bible ask you hard questions and ask them right back. Get stuck into a good discussion about what something might mean, read a commentary or two, phone a friend, draft in a scholar.

Flaky Listeners?

I don’t know if this is true or not, but I think that the sloppy practices that we’ve got into is to do with an idea that we think people don’t want to sit through something that might be seen to be dry or overly academic. Is it because we’re so desperate for people to come in and stay that we think we need to make every talk entertaining? Or is it because we think that we’re dealing with a generation that can’t concentrate any more? I can promise you that anyone who can binge watch Netflix or play a video game for 24 hours non-stop has no problem concentrating. They’ll just concentrate on what they want to concentrate on. Like eating junk food.

Personally, I don’t think we need to pander to a fast-food culture, especially as I see so many people come alive when they’re taught the Bible by people who love it, believe it, and understand the power of it for knowing God and knowing ourselves. I think it’s about changing our cooking and eating habits.

Changing a Nation’s Eating Habits

For some while now I’ve been interested in Jamie Oliver and his mission to change the eating habits of whole nations. I love food and I love the effect of good food on people and I get what Oliver is doing. I think he’s right to want to start a “Food Revolution.” I recently watched his Ted Talk on this in the US.[2] You can see his passion in this talk. I actually think there are things the church can learn from him, precisely because his mission is to change a nation’s eating habits, and it strikes me that this is the task before us with the Bible.

The two things he focuses on are education and producing delicious food. Teach people why good food matters, let them taste delicious food, and then teach them to cook nutritious, delicious food for themselves. A simple vision.

It’s fascinating watching his Ted Talk peppered with what I associate with prophetic language—the time is now, the time is ripe, people are ready for change. I feel the same about biblical literacy and theological education. People are hungry and bored, tired of eating food that leaves them sluggish, and ready for something more engaging. It will undoubtedly mean more work for everyone, but it will be so worth it.

So just to carry on with the food analogy a bit longer…

When you’ve become used to/addicted to fast food, you need to do some work to change your palate and your cooking and eating habits. It’s about changing your expectations of food: the buying, the preparation, the eating. Finding spiritual food requires more time than getting a sugar-hit or a salty, cheesy burger delivered to your door while you lie on the couch in your pj’s watching Netflix. We all might enjoy a sugar-hit or a burger moment, and we may have had the spiritual equivalents of these moments. But the general rule for eating spiritual food from the Bible is that it requires foraging, simmering, picking through bones, marinating, refrigerating, smoking. It’s food that will take time to bring out rich and deep flavours.

One of the things that Oliver disturbingly demonstrates is how milk is now served in American schools – it now has added sugar and flavours. So rather than just plain milk, children are being loaded up with pounds and pounds of sugar because someone somewhere decided that milk on its own was no longer appetizing. When does something served as “milk” cease to be nutritious and thus not really milk at all?

I’m one of 5 siblings and my mum in her day was a health freak. We had very little sugar at home, no white bread, no crisps etc. As a result, we loved eating fast-food. Whenever we could we binged on it. I used to swap my horrible home-made brown bread and cheddar cheese sandwiches with Clare Taylor who had white bread and Dairylea. Yum. That was primary school. The long-term result though is that in reality Mum taught us all how to cook good food and to love it. She passed on good eating habits.

I wasn’t nearly as conscientious with my kids (who all also love fast-food!). I did read about making kids eat a tiny bit of what they say they don’t like though, and I tried that because I didn’t want fussy kids. It totally works and eventually gives them the ability to eat what is put in front of them. A lesson on how eating habits can be formed over time.

Oliver has a simple formula: education, letting people taste delicious food, and teaching people to cook for themselves. The parallel for us is this: education (why Bible study/scholarship matters and why I should bother), letting them taste delicious food (making Bible study and theology as fascinating as it really is), and teaching people to cook (giving them skills for their own study).

Serving up proper meals and changing our cooking and eating habits will mean a fitter, more robust, more flexible, more resilient, long-lasting body that is the church. It’s totally within reach and I personally think, along with Jamie Oliver, that the time is ripe.

[1] This is linked to the idea of the perspicuity (or clarity) of Scripture that is inherent in the Scriptures themselves. This is a Protestant principle found in such texts as the Westminster Confession of Faith, although even there it is stated that ‘All things in Scripture are not alike plain in themselves, nor alike clear unti all: yet those things which are necessary to be known, believed and observed for salvation, are so clearly propounded, and opened in some place of Scripture or other, that not only the learned, but the unlearned, in a due use of the ordinary means, may attain unto a sufficient understanding of them.’ (7.1) My italics. Scripture can lead a person to faith, learned or unlearned, but is not necessarily ‘plain’ in all things.

[2] https://www.ted.com/talks/jamie_oliver/transcript?language=en

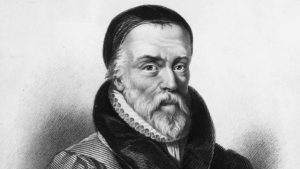

William Tyndale translated the Bible into English in order that ‘the boy who drives a plough (would) know more of the scriptures’. And he was executed for it!Today, almost 500 years after his death, it’s easy enough to pick up an English Bible, but our secular C21

William Tyndale translated the Bible into English in order that ‘the boy who drives a plough (would) know more of the scriptures’. And he was executed for it!Today, almost 500 years after his death, it’s easy enough to pick up an English Bible, but our secular C21